_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________Religious Terminology of the Welsh

Valuable evidence as to the nature of early Welsh religion may be gathered from a brief examination of the religious terminology of the Welsh people.

The late Professor Huw Williams , a great authority on the early British Church, writes:

The Faith in Britain was the Faith of Western Europe generally; its Church had the same organisation of ministers. in which Bishops and presbyters became Sacerdotes , the Lord’s Table, an altar. To these Sacerdotes belong the power of binding and loosing. Behind all was the wonderfully powerful force of Monachism.’

And again:

‘Throughout the west one language universally prevailed in religion. Gildas quotes a Latin Bible, and the literature he read was Latin. Long before Gildas, even St Patrick, the Apostle of Ireland, though a Welshman, wrote in Latin.’‘The native language it would seem, was only used for preaching to the people. The result of this close contact with the Latin world- if one may thus describe the early ecclesiastical situation – was that out religious language has become steeped in Latin’

The following short list of the principal Welsh religious and ecclesiastical terms will illustrate this; and though the list may be dry reading to some of my readers, it is desirable that the point should be made clear before proceeding further.

eglwys ecclesia

offeriad,offrwm, offeren Eucharistic sacrifice

baglawg baculus ecclesiastic entitled to carry a crozier

Periglor Parochus, Parish Priest

Trindod,or trinted Trinitas

Bedydd Baptismus

Senedd Synodus

Clerigwr Clericus

Pregeth Praedicatio

Cardawd Caritas

Gosper vesper

Gras gratia, grace

Crệd credo

Erthygl articulus

Crysfad chrisma (Old Welsh name for Confirmation)

The second Sacrament, says Canon Griffith Roberts in his ‘Grammadog Cymraeg’.’is the Bedydd Esgob a clwir Crysfod.’

Cablyd,Difiau Cablyd capillatio

(The monks were tonsured on this day, Maundy Thursday)

Calan Caledoe

The calong par excellance was January 1st,, but we also have calan mai and calan Gauaf)

Ynyd initium(dydd Mawrth Ynyd= Shrove Tuesday)

Cabidwl Capitulum cathedral chapter

Urdd ordo

Garawys Quadragesima Lent

Segyrffig (now obsolete) sacrificium

Ystwyll Stella (star)Epiphany festum stella

Pgiol vial

Paeol holy water stoup

llện legend

elusen eleemosyna

y fall malus the evil one,

naf numen

pader paternoster

gwers versus

benedith benediction

Merthyr martyr

Llith lectio

Nadolig natalis

Paradwys paradisus

Pechod peccatum

Addoli adoro

Achub occupo

Arawd oratio

Ysbryd spiritus

Plygain pulli cantus;(night song)

gwỹl vigilio

swyno meaning ‘bewitch or charm’

(means makingthe sign of the Cross Signo- to bless

dwfr swyn holy (blessed ) water

sagrafen sacramentum

allor altare

ysymmuno ex-communio

uffern inferna

dofydd domitor, divinity

cappan cope

cappa;cymun communion

cyffes confession

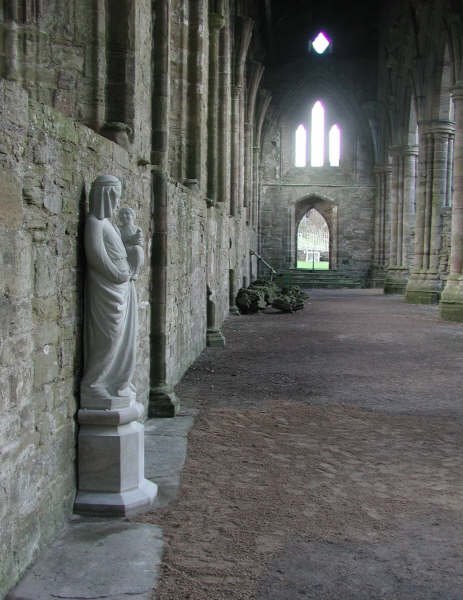

mynach monachus

mynachlog monachi locus

Lloc locus part of Welsh placenames.( A notable use of its use as signifying a monastery is contained in the Black Book of Camarthen.

Ni phercheist ti creiriau,Na lloc na llaneu

You have not respected relics, nor monastery nor churches.

It also survives in the word ‘llech’(sometimes erroneously interpreted in Welsh Place names such as ‘stone’ or ‘slate’) eg Llechgenfarwydd, Llechydwr, Llechgomer, Caellech, Penllech)

Cil, Cill Cella

Columba was called Columncille- thedove of the cell)

Kilmuine St David’s Cell (Kilmynyw)

Disart,disserth from desertum, lonely place, monk’s retreat

Caregl calyx, chalice

cộr chorus

clas classus,clausum old cathedral chapter

clos (cognate word) Cloister, close monastery-clausus

syber superbus

Abad I’w glosydd rhwng bedw gelision’.

We could go on indefinitely with the list of Welsh religious terms derived from Latin, but these examples are enough to prove how largely we have borrowed from the parent language of Welsh Christendom. So that, apart from the evidence of Welsh history, we have the clear evidence of language .The Welsh word for ‘religion’ crefydd is a notable instance of this. The word crefydd in pre reformation times meant, with scarcely an exception , not what it means nowadays, the abstract principle of religion, vague enough to incorporate any kind of religious belief, but the definite profession of religion in the monastic sense. It meant the religious life, consecrated and followed under the organised discipline of the Catholic Church. Crefyddwr meant those who were under religious vows. In early Welsh literature crefydd was of the masculine gender, but in modern Welsh it is feminine. In fact it represents in its change of Gender the evolution of religious faith from the dogmatic and definite to the undogmatic and indefinite.

The Puritan,’a good man in the worst sense of the term’ may be said to have changed the meaning with the change in gender.

Crefydd Gwyn e.g. meant The Order of White Monks,-crefydd being the specific term for a religious order.This is the invariable meaning attached to it in our oldest Welsh literature , such as the Welsh Laws,The Chronicles and the San Greal and others.

The old monastic or Catholic connotation of the word passed away with the supression of the Welsh monasteries.

Dr Hartwell Jones, the author of Celtic Britain and the Pilgrim Movement-throws a flood of light on the Catholic Character of early and mediaeval Welsh religion-writes as follows:

It is difficult to conceive that Catholicism at one time permitted Welsh habits of thought ; that its beliefs were jealously cherished; that its theological terminology is woven into the very warp and woof of the Welsh language. Indeed from the third century to the sixteenth, Wales adhered to the old Faith as rigidly as Spain or Italy at the beginning of the nineteenth. This revulsion of national temperament and reversal of a national bias is one of the strangest psychological phenomena of English history’.

After quoting the evidence of foreign writers in the sixteenth century, to the effect that this country was strongly and avowedly Catholic, he goes on:

‘Catholicism appealed to the poetical temperament of the Welsh. Underneath the surface, there lies in the Welsh nature a vein of mysticism which three centuries of Puritanism have not succeeded in eradicating. A love of symbolism also, an eye for the artistic aspects of the Christian religion, a fervid imagination, and an impressionable temperament, would naturally find expression in the Catholic Creed and Catholic ritual; in the stately aspect of the Christian year, the unbroken round of services, the religious acts by which Christian truths were expressed, and in the warm colouring of Catholic ceremonial. Many instances might be cited from modern Welsh literature by the pens of writers who would repudiate any sympathy with Catholic belief or practice, yet betray and instinctive harmony with the Catholic spirit.

A more scientific study of Welsh history, and the renaissance of genuine interest in archaeology and antiquarian lire, have led a new generation of Welsh people to grasp the truth that the heroic period of Welsh history and the golden age of Welsh literature sprang from the heart of the Catholic spirit

And specially prominent in this ancient literature is the spirit of loyalty to the See of Rome, deep even passionate devotion to the Blessed Virgin and the Holy Mass.

And this evidence is not limited to any particular period; it is true not only of mediaeval Wales, but of early Wales as well. Of this early period of Welsh exxlesiastical history, Stephens, in his Literature of the Kymry writes:

“The Church had become powerful in Wales, as well as over the rest of the civilised world. Papal theology possessed and directed the human understanding , and gave its impress to all opinions. We have one striking instance of this in the Awdl Fraith which is evidently an ecclesiastical production of the romance era. This might have been inferred from the tone of the composition, its allusion to the afrilat cyssegredig and its Latinised diction.

He even considers that the immortal Arthur himself, the religious hero, the greater part of whose memorials were found in convents, is partly, at least, a being of monastic creation.

‘The Catholic Church’ he adds,’was now in its glory and at the height of its power ;and now, as at all times, was most studious to conform itself to the improvements of society. It mingled with all things without excluding any; and in Wales, theological modes of thought, feeling and expression were everywhere displayed.

‘The Mabinogi’ of Taliesin is replete with theological expressions.’

He attributes the spirit of the old Welsh romances not to the lay bards, but to the inmates of a monastery:

‘Of the fine and high tones sentiments which breathe through the Mabinogion, we have no traces in the works of the bards;they must therefore have emanated from the clergy.’

This , it may be added, is specifically true of the tales of the San Greal, which was supposed to be the cup out of which our Lord is said to have drunk before his crucifixion, or which contained His blood.

Our earliest Welsh literature, in spite of its mythological background and martial atmosphere is by no means lacking in definite evidence of a Catholic age. Scattered phrases and sporadic allusions, as well as explicit references to Catholic truths, all point steadily in the same direction.

The ‘Book of Taliesin’ e.g. one of the ‘Pedair Cainc y Mabinogi’(4 ancient books of Wales)contains very distinct allusions to the religious beliefs of the age.

The Eucharistic Sacrifice (Holy Communion) is designated as the Urddol Segyrffic, the honoured Sacrifice of the Mass.And the Awdl Fraith the ‘Ode of Varieties’, attributed to Taliesin, the Holy Eucharist as Stephens says is referred to as the afrllad cyssegredig.

‘

Again in ‘Air y Mynydd’, a fantastic imaginative poem of great antiquity, preserved in te Red Book of Hergest, the Holy Communion is mentioned in Connection with Confession which is regarded as an essential principle of the religious life.

The end of alle thing in Confession for the sayke of God, make a full confession.

Again the Blessed Sacrifice is desired by the writer as a shield of salvation against the dread decree of the Day of Judgement-

Rhag gormeil golaldydd brawt’

Llywarch Hện , a sixth century prince and poet, and probable priest as well, writes:

Before I was a fair priest Kyn bum kein vaglawc

I took part and made prayerful compassion Bum kyffer eiryawe

Before I was a fair priest Kyn bum kein vaglawc

I was bold Bum by

I was entertained in the convent house Am kynnwysit yg kyuyrdy

Of Powys, Paradise of Wales Powys Paradwys Cymru

The title in connetion with Llwywarch (hện) refers, in the opinion of Professor High Williams, the author of Opera Gildae, to his ecclesiastical status-senior.

But apart from the external corroboration,the words of the poem itself show that the author was a priest.

In consequence of this ecclesiastical significance of hện , he quotes Pawl Hện , the Welsh name for Paulinus, but it is doubtful if this is a true parallel. Pawl Hện seems to be merely the Welsh form of Paulinus with the Latin terminal lopped off. In fact, there is on the borders of Cardigan (Dyfed) and Camarthen , a church dedicated to Paulinus called Capel Peulin. Paulin or Peulin could easily become Pawl Hện, in which ‘Hện’ is, of course a mere phonetic addition.

In the Book of Taliesin (xvii) we have the following lines:-

There will be no priest ‘Ne byd effeiriat

The wafer bread will not be consecrated Ny bendieco afyrllat

The perverse will not know Ny wybyd anyguat

The seven faculties(=Sacraments) Y seith lafanad’

The primary meaning of llafanad is ‘intellect’ or ‘interllectual faculty’ hence its meaning of faculties in the sense of means of grace, Sacraments.

Anygnat is an early Welsh form of anynad from an and ynad,unreasonable contentious, perverse.

A poemin the Black Book of Carmarthen attributed to Meigant a bard and saint of the sixth century, contains a curious proverbial saying:

Ni chenir bwyeid ar ffro’

Mass is not sung on a retreat

In the Book of Aneurin a sixth century document, we have an interesting collection of phrases , referring to different religious subjects, but which, if taken together, point to a decided Catholic environment. They are taken at random:

The Trinity in Perfect Unity

The shaft, heavy as a crozier of the principal priest (Bishop)

They went to the Llan for penance.

A Llanfawr full of desire for Baptism

In spite of their meagreness, the beliefs and customs of the Catholic Church in early Wales peep out quie clearly between these ancient lines.

The last quotation in particular seems to point to a period of high antiquity, when the country was being gradually from Druidic paganism to the Christian faith.

The process of conversion from Paganism was always expressed in Welsh literature as ‘desire for Baptism’.

The following conception of S Peter at this very early period is a convincing tribute to the antiquity of the Catholic tradition among the Welsh:

I love to praise Peter Caraw voli Pedyr

Who can bring Peace! A vedir tag tew!(Skene) ‘Tag’ seems to be an early form of ‘tanc’ assuming the reading to be a correct transcription- and tew is a form of taw tewi.

Again:

Oret y Duw buw budyeu Pray to the Living God

Am byd ryd radeu for benefits.through the

Drwy eiryawlseinhau (i.e.seintiau) Intercession of the Saints.

The influence of the Latin on early Welsh phraseology is well illustrated by the first word of this verse-‘oret’ from oro.In fact the Latinized diction of the ancient Welsh bards is quite noteworthy.

We have, unfortunately, very few relics of pre-Norman Welsh script to fill up the long gap between the age of Taliesin and Gildas. And the literature that blossomed forth under Norman influence or at least in Norman times. But even the Welsh glosses and verses on the Cambridge ‘Codex of Juveneus’ (ninth century) which probably came from the monastery from Llancarvan, contain englynion of a highly religious character. The text as we have it is sadly imperfect , but evidence is made to the Tindaud, Bedit, and Mab Mair: The Holy Trinity, Baptism and the son of Mary.

If we had the full text ,we should doubtless have ample evidence of the ancient Faith and its liturgical and devotional forms among the old Kymry

No comments:

Post a Comment