The subject of the religious beliefs of the Welsh people in the Middle Ages is one that has not been adequately presented to the modern Welsh mind. Were it not for the industry and zeal of our antiquarian societies , it is doubtful whether the student of Welsh history would succeed in passing the charmed barrier of the Purital era, which to most Welshmen has been hitherto the terminus a quo of all that is greatest and most fruitful in Welsh History. It has not yet quite dawned upon the ordinary Welsh student that the Puritan era, on the other hand, and for weighty historical reasons , may be quite truly viewed as the terminus ad quem of a golden period of our national history.The deeper we delve into the records of the past, the more we perceive the profound character if the religious change that took place after the Reformation-rapidly in England, but slowly in the principality of Wales.

In the following pages, the main facts bearing on the religious life of the Welsh people in pre-Reformation times are placed before the reader . It is not pretended that these facts are being put on record , for they are already perfectly well known to the historical student.

The writer merely claims that the facts are put in their proper setting. Within the natural limits placed on a modest brochure of this type it is not possible to go into details: in fact one of theproblems that the writer finds himself obliged to solve at every turn it,not what he must put in, but whathemust leave out Welsh mediaeval literature is a very difficult field of research, and it is by no means an easy task to present the results of ones investigations in the form of a summary. This is particularly the case with religious belief , where the evidence is often so elusive and impalpable , so hard to tabulate and classify.

There are documents in Welsh history in which the verbal references to definae religious beliefs and customs are of the scantiest; and yet if we divest ourselves of the legal conceptions of evidence, we often rise from the study of such documents with a most definite conviction of the real character of the religious system that stands behind it and reveals itself through it. It is difficult to know how anyone that is even moderately acquainted with welsh historical records Can fail to arrive at a clear conclusion as to the character of the old religion (y hen fydd) of the Cymry.And yet the following quotation from Mr Willis Bund’s Celtic Church of Wales

Nonconformity comes closer to the old tribal law than anything else. A Welshman, who studies his country’s history sees that there is nothing so near the old Welsh Religious System than Nonconformity.This is one of those strange historical judgements that take one’s breath away. Some of our leading Welsh historians are apparently afflictedwith colour blindness ,for, however real their sympathy for the Protestant Principle, this vision of a primitive non-conformity established around the altars of the Romano British Church , and offering the Sacrifice of the Mass, is not one that has been vouchsafed to them. It is hard to understand in what cryptic sense modern non-conformity can be made to resemble the religion of the old Cymry;but, as the argument has now been put forward with all the apparatus of historical learning the best way to dispose of this primitive anachronism is to produce afresh the evidence of history.

It may be mentioned in passing that the antithesis between the Celtic and the Latin type of Christianity has been greatly over-exaggerated. It is quite legitimate to talk of a Christian type of Christianity and a Latin type , both ancient and modern. Celtic civilisation with its political, social and legal institutions , differed in some important respects from Latin civilisation , and had a character of its own. But these differences, however important in the eyes of a historian , cannot reach a point where they are likely to affect the essential character of Catholicism They are purely external, incidental, subsidiary.

Those internal varieties or aspects of the one great whole, due to the national ethos, do not touch the question of the unity and the Homogeneity of the Catholic Body. The tribal idea of Christianity was in no respect inconsistent with the institutions of the Catholic Church. The Laws of Hywel dda were framed for a tribal of society. But the Catholic Church , with its long, established institutions was the living centre of that society- the soul that dwelt serenely and fruitfully in the tribal body.

A Welshman who studies his country’s history without blinding himself with preconceived notions will look in vain for historical evidence of the idea that early Celtic religion was a kind of Protestantism ‘born out of due time’.

The religious history of the mediaeval period is not so well known to the general public as the earlier-the age of the Saints; and yet Welsh Mediaeval literature reflects very fully and unambiguously the inner life of the Catholic church and the religious devotions of the Welsh people.

Much of this evidence is contained in our bardic literature so much of which is fortunately preserved in that great corpus of Welsh literature, both poetry and prose- the Myfyrian Archeology.

Welsh Bardic literature from the eleventh to the sixteenth centuries is full to overflowing with the most definite and spontaneous testimony to the religious faith of our forefathers.

Catholic allusians in Welsh Bardic Literature

The Sacrifice of the Mass the invocation of saints. The doctrine of purgatory, auricular confession, penance, fasting, the Blessed Virgin Mary, extreme unction , the supreme authority of the See of Peter- these are the constant and essential elements in the religious as well as the secular poetry of mediaeval Wales.

Dr Rhys Phillips . in his book on The Romantic History of the Monastic Literature of Wales, says that ‘a close examination of the literature of the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries reveals most of the bards as pious Catholics, working in unison with, and receiving much of their information from, the monks who had generously espoused the Welsh national cause, and suffered for it’.

The scores of poems to ‘Mair’(Mary) , ‘the Virgin’, to the saints, and to the various abbots of contemporary monastic houses,form a library of Roman Catholic poetry, probably unequalled in any country of the same size at that era. The Elegy of St Cunedda is in the Book of Taliesin ; while addresses, odes,or cywyddau to SS Beuno, Brigid, Cadoc, Cawrdaf, Collen, Curig, Cynhafel, Cyntog, David, Dwynwen, Einion, Gwenfrewi, Illtud, Mair Magdalen, Margared, Mihangel-next to Mair in popularity- Teilo and others, have been copied and recopied into a large number of manuscript collections.

Welsh literature, in fact,owes its noblest and earliest achievements to the old Welsh monasteries. This fact is at last becoming increasingly evident to the student of Celtic literature, but for the sake of those who are not students in this particular branch, this must be emphasised afresh , for it is very closely connected with the subject of this treatise.

The literary activity of the Welsh monasteries covers the whole period from Gildas to the dawn of the Tudor period.

Welsh Laws of Hywel Dda

It is true that the courts of the Welsh princes were to some extent centres of literary life. This is evident from the testimony pf the Welsh Laws of Hywel Dda. But this qualification must be added: that the literary interest was probably confined to the two departments of (1) bardic lore of a somewhat restricted and professional kind and (2) genealogical records.

Welsh Monasteries as Centres of Culture

The monasteries were undoubtedly the principal centres and courses of culture. The Celtic literature that influenced Europe came from the inmates of the monastery.

The very earliest writings that have survived, such as the De Excidio Brittanicae of Gildas, which is in a sense our first Welsh history, and Nennius’ Historia Britonum both hail from some monastery in Glamorgan.

It is unfortunate that the early devotional literature of the Cymru survive in such attenuated form. We would gladly exchange a whole library of the ponderous and dreary Genevan theology for a few copies of a Welsh Missal.

These were, of course, the first objects of attack by the iconoclastic bigots of the Dissolution period.

Not only did the monasteries produce a very considerable portion of our early literature such as the ‘Lives of the Saints’ the ‘Romances’ and the Chronicles, but they also preserved and transcribed old documents which would otherwise have perished.

Writers such as Gerald the Welshman (Giraldus Cambrensis) Caradoc of Llancarfan, and the compiler of the Liber Landavensis,(Book of Llandaf) had access to ancient records, which they adapted to suit new literary and historical theories, or to meet new ecclesiastical circumstances.

The basal document of all Welsh history is the Annales Cambriae . This is supposed have been compiled by St David’s monastery, a conclusion which is drawn with some confidence from the strong local colouring of some of the entries contained in it. From the Scriptorium of Llandewi-Brevi- memorable for the great council with which the name of St David is connected-came the valuable Llyfr Ancr-The book of the Anchorite.

Camarthen Priory

Perhaps the most interesting literary document in connection with Welsh history os the Black Book of Camarthen the oldest extant manuscript in the Welsh language. It was written in the twelth century by a Welsh Augustinian monk in the Priory of Camarthen.

From the same corner of Wales emanated the famous Black Book of St David’s.

Margam Abbey

Margam Abbey is well known for its Annales de Margam a chronicle that covers the period AD 1147-1232.

Many of the treasures of this old abbey are preserved in the British Museum, still unpublished. These include a twelfth century copy of the Domesday Book, the Gesta Regum and the Novella Historia of William of Malmesbury, and the History by Geoffrey of Monmouth.

The Margam Collection of charters and deeds contain probably the most complete original series in existence relating to one monastic establishment. It was at this famous abbey that the Red Book of Hergest was first heard of, which contains so many exquisite old Welsh romances. It was from this source that Lady Charlotte Guest translated the Mabinogion.

Llandaff Cathedral

The mother church of the diocese, Llandaff, rejoices in being the source of the gospel of Teilo , cometimes called the Book of Chad ;also of the LiberLlandavensis which is one of the most valuable ecclesiastical documents in Welsh history.p 12.

It was compiled early in the twelfth century, but it contains very much older material of unequal value.

Neath Abbey

Neath Abbey, one of the first Cistercian houses in Wales, has lost nearly all its literary treasures. But in the fifteenth century the monks had a copy of a manuscript called the Grail. This was said to be the great San Greal, the romance of the Holy Grail.To this abbey is also attributed the Welsh version of the Parvum Offerium Beata Mariae.

The editor of the Welsh historical Manuscripts Report is of the opinion that the Book ofTaliesin one of the Four Ancient Books of Wales came originally from Neath.

Strata Florida

Strata Florida, the Westminster Abbey of Wales in the Middle Ages, was famous for its learning. It was here that Brut y Tywysogion,the Chronicle of the Princes, was compiled. It appears that the monks of Strata Florida compared notes at regular intervals with the chroniclers of the Abbey of Aberconway, so as to ensure a correct account of historical events. ACodex of the Annales Cambriae is also attributed to these monks, as well as parts of the Red Book of Hergest.

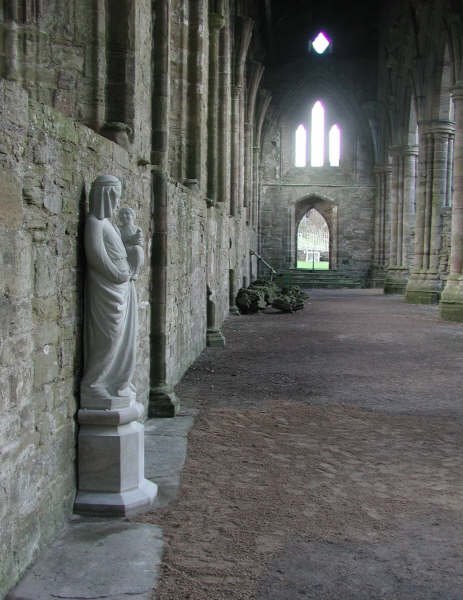

Valle Crucis-near Ruabon

Valle Crucis is perhaps the most picturesque of all the ruined abbeys of Wales. It was known for its generous patronage of men of letters. Its praises have been sung by the most prominent bards of the Middle Ages, such as Gutto’r Glyn and Guttyn Owain,whose history and bardic compositions are closely associated with the annals of Valle Crucis. Here lie the mortal remains of Iolo Goch, the Bard of Owain Glyndwr: and Iolo’s hymns were chanted in the monastery choir. It appears that a White Book once belonged to this abbey, but is now lost or burned.

Strata Marcella

Strata Marcella, Ystrad Marchell, A Cistercian house in Powys is supposed to have been the source of the thirteenth century Life of Gruffydd ap Cynan.

There in the British Museum is a fine collection of Welsh poetry, of which Dr Gwenogfryn Evans writes that ‘judging by the orthography, its original was written in the thirteenth century, inferentially at Strata Marcella, by the scribe who wrote the Book of Aneurin’.

The Dream of Rhonbury is supposed to have been, in its present form, written at this abbey; also the Mabinogion of the White Book of Rhydderch.

The Black Book of Basingwerk is an echo of the literary activity of the abbey of Basing. This is a copy of the Brut of Caradog by Gutyn Owain who brought the record down to his own day.

And so we could go on indefinitely; but this brief list of some of the principal monasteries of old Wales, and their literary labours, is enough to convince the reader that Welsh literature owes an enormous debt to the monastic houses, and that it was generously fostered by the Church.

Sunday, August 30, 2009

Catholicism in Mediaeval Wales-Part I-J.E.Hirsch-Davies

Labels:

Camarthen,

Catholic Wales,

Hirsch-Davies,

Neath Abbey,

Valle Crucis

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment