St Cynfarch.

St Cynfarch.

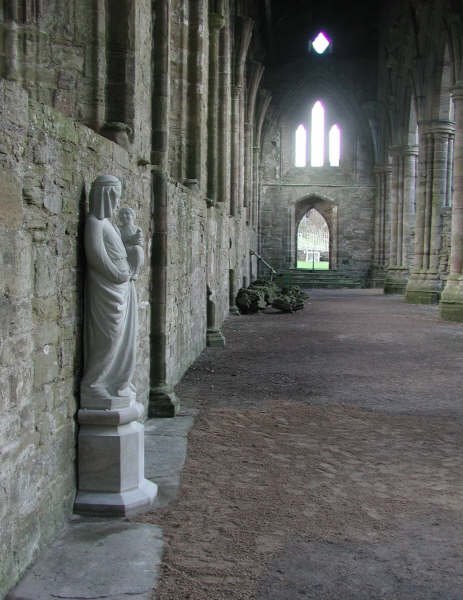

Penmon Augustinian Priory in Middle Ages-probably similar scale to St Kynemark's(Cynfarch's)

Penmon Augustinian Priory in Middle Ages-probably similar scale to St Kynemark's(Cynfarch's) _________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________"This is the truth, if a monk regards contempt a praise, poverty as riches, and hunger as a feast, he will never die." Blessed Macarios of the Desert

Cynfarch Oer, King of North of England and Welsh Saint

Cynfarch's (Oer) has a strange title which means 'the Dismal'. He was the son of Meirchion Gul, the King of Greater Rheged in the North of what is now England and, upon his father's death, inherited the Northern portion of his Kingdom. Cynfarch lost the South of the country to his brother Elidyr but soldiered on in what is now Scotland. About AD 550, King Senyllt of Galwyddel seems to have been expelled from Galloway and was forced to seek refuge on his island stronghold of Ynys Manaw (Isle of Man). King Cynfarch is the most likely aggressor, especially as a number of places in the region are associated with him. Susan Mayes, however, to his possible identity of a saint and poet and a softer side to his personality, and his conversion to Christianity and founding of his ‘desert’ or White Martyrdom at the lower side of Offa’s Dyke at the area we know as St Kynemarks. One mile north of Chepstow.

She discusses on her web page the ‘Canu Heledd’, the song of Heledd (you remember we discussed her and her settlement at Llanheledd near Pontypool) Llanhilleth. The pagan Anglo Saxon Mercians pillaged and ravaged the kingdom of Powys and destroyed King Cynddylan. Susan suggests for various reasons, the poet may have been Cynfarch.? Possibly Cynfarch had been educated in one of Dubricius’ monasteries, as were so many of the Welsh saints, and we know he was a disciple of Dubricius (known as Dyfrig). Like King Tewdrig he had to follow his calling as King and but may have passed on his Kingdom when his son Urien reached his maturity and had the youth and strength to defend his people, as Tewdrig had done with Meurig. Cynfarch could have then dedicated himself to his love of history and poetry in his later years.)

Susan writes

‘Highly skilled in the Welsh poetic tradition, fond of contrast and irony, a keen observer, compassionate, acknowledging women within his cultural limits, a man who loved Powys: who and what was the poet?

An educated man of his era was almost certainly a trained bard, a churchman or a member of the ruling elite. It may be that the Canu Heledd poet was of privileged rank, associated with a royal house of Powys in the ninth century and formally trained as a professional poet. It is not impossible that he was Cyngen's historian and the writer of the Elise's Pillar text, Cynfarch. ‘ (This Pillar and its poetry is to be found at Valle Crucis Abbey near Llangollen in North Wales.)

This is her website, but you will have to c and p

http://www.castlewales.com/canuhel.html

Ystafell Gyndylan ys tywyll heno Cynddylan's hall is dark tonight.

heb dan heb wely. without fire, without a bed.

wylaf wers. tawaf wedy. I will weep a while, be silent later.

Ystafell Gyndylan ys tywyll y nenn. Cynddylan's hall, dark its roof

gwedy gwen gyweithyd. after its fair company.

gwae ny wna da ae dyuyd. Alas not to do good as it comes.

The Welsh 'Martyrdoms' and the Desert Fathers

St Cynfarch’s ‘llan’ or religious settlement on the banks of the Wye, probably followed all the previous foundations of ‘llans’ which I have written about before (the preparation of the land, the fasting, the delineation of the wall in separating the earth from heaven within etc) and when Cynfarch’s son, Urien took over from him as monarch, the older King lived out his life in his special monastery in peace and tranquillity. If Susan Mayes hunch is correct, it might be that the Canu Heledd was written here. We learn that at some time, possibly as a child,but not certainly so, as he may have discovered a vocation late, he became a pupil of St Dubricius-perhaps at one of the saints many monasteries. The early Welsh (romanised Britons) designated the finding of their plot of land for their ‘desert island’ as a Martyrdom-giving their life to God. Red Martyrdom was literally giving their lives for Christ with God and Blue or Green Martyrdom was actually the life spent on that special site, dedicated to the service of God. King Cynfarch seems to have been proclaimed a saint at this very early time, possibly because of the wars against the Saxon Mercians

and then retiring to a life of holiness after a lifetime of battles, in early life as a soldier and young king and in later life, being forced to defend his kingdom.

The Desert Fathers,St Anthony and St Augustine

"Sit in thy cell and thy cell will teach thee all." Father Moses,

We have recently learned how the Augustinian Friars of Newport and elsewhere in Britain admired the Fathers of the desert and sought to copy their hermit existence. The ‘Desert Fathers’ were Hermits, Ascetics and Monks who lived mainly in the Scetes desert of Egypt, beginning around the third century. They were the first Christian hermits, who abandoned the cities of the pagan world to live as hermits. These original desert hermits were Christians fleeing the chaos and persecution of the Roman Empire's Crisis of the Third Century. They were men who did not believe in letting themselves be passively guided and ruled by a decadent state. Christians were often scapegoated during these times of unrest, and near the end of the century, the Diocletianic Persecution was more severe and systematic. In Egypt, refugee communities formed at the edges of population centres, -far enough away to be safe from Imperial scrutiny.

Fasting and Abstinence

In 313, when Christianity was made legal in Egypt by Diocletian's successor Constantine I, a trickle of individuals, many of them young men, continued to live in these marginal areas. The solitude of these places attracted them because the privations of the desert were a means of learning self-discipline. Such self-discipline was modelled after the examples of Jesus' fasting in the desert and of his cousin John the Baptist (himself a desert hermit). These individuals believed that desert life would teach them to eschew the things of this world and allow them to follow God's call in a more deliberate and individual way.

Thus, during the fourth century, the empty areas around Egyptian cities continued to attract others from the world over, wishing to live in solitude with a reputation for holiness and wisdom. In its early form, each hermit followed more or less an individual spiritual program, perhaps learning some basic practices from other monks, but developing them into their own unique (and sometimes highly idiosyncratic) practice. Later monks, notably St Anthony, developed a more regularized approach to desert life, and introduced some aspects of community living (especially common prayer and meals) that would eventually develop into monastic hermit style life Many individuals who spent part of their lives in the Egyptian desert went on to become important figures in the Church and society of the fourth and fifth century, among them Athanasius of Alexandria, John Chrysostom, and John Cassian. Through the work of the John Cassian and Augustine of Hippo the spirituality of the desert fathers, emphasizing an ascent to God through periods of purgation and illumination that led to unity with the Divine, deeply affected the spirituality of the Western Church and the Eastern Church. For this reason, the writings and spirituality of the desert fathers are still of interest to many people today.

We can therefore see that both the Celtic Spirituality of the Martyrdoms and that of the desert fathers led by St Anthony (Athanasius) and others had their root in the same tradition. Losing themselves in the love and worship of God, becoming closer to him by separating themselves from a wicked world . In Welsh practice, marking out the area of their heaven by means of a wall, which contained their piece of the desert, by fasting and prayer for forty days and nights.

Menace of the Pagan Saxons

There is no doubt at all that the initial Saxon onslaught left people shaken. Meurig had managed by endless battles and the help of the Wyche and Dean Forests, which the pagan Saxon feared, so that only certain Roman roads had to be defended, to keep them out of Monmouthshire, after his father the Blessed King Tewdrig had been martyred by those who had been attacking his llan at Tintern (Ty-nderyn-the ‘House of the King’).Monmouthshire (or the Gwent kingdoms as they were then) received a great many refugees from over the border and much of it remained free from Saxon interference until well into the seventh and eighth centuries so it’s Christian basis was safe there, possibly why Cynfarch chose to come to comparative safety here. Much of this remains conjecture, as we have few records, many having been destroyed throughout the years, but safety is surely a very good reason for founding a desert settlement or llan dedicated to a peaceful existence and end. Moreover the settlement of St Cynfarch above Chepstow seems to have had privileged or special status even into Norman times.

Reform and restructuring by the Normans of the llans within the original faith of the Desert Fathers and St Augustine.

When the Normans arrived the Benedictines arrived with them to found the priories in Monmouthshire, but they also began to regularise the Welsh monastic settlements they found there. This was not a kind of ‘Jack boot’ measure destined to shoehorn Welsh monasticism into a Norman understanding, but rather perhaps to reform Welsh practices which over the centuries had deviated somewhat from the original doctrines of St David and the early Welsh saints. There were Druid practices in some places, and what was important for the whole universal church was that the teachings of Christ were adhered to and not mixed with more ancient heresies and, in truth, the Normans did this by reminding them of the spiritual leadership of their inspiration, the Desert fathers, and through them to St Augustine of Hippo, a giant Church teacher, who had written a Rule based on these hermit practices and St Anthony.

St Augustine, therefore , became the pattern for the host of different Welsh ‘llans’ and these communities were helped to build stone churches, if they did not have them already, but had proper priors and a hierarchy, responsible for the upkeep of buildings and souls in the area. The other Order which arrived in Wales and were enthusiastically received by them was that of the Cistercians, of whom we shall speak later. The Cistercians, a more austere Benedictine Order ,worked physically for a living, sought out remote places to worship,live and work and had as a spiritual father the saintly Bernard of Clairvaux. They left a deep impression on Gwent (including Welsh Herefordshire) from their communities at Tintern, Grace Dieu, Llantarnam and Dore.More about them later.

The Augustinians took over the administration of the following places in Wales:

In North Wales: Bardsey Abbey, Gwynedd

Beddgelert Priory, GwyneddPenmon Priory, Anglesey, Puffin Island Priory, Gwynedd, St Tudwal's Island Priory, Gwynedd

In Mid Wales: Carmarthen Priory, Dyfed, Haverfordwest Priory, Pembrokeshire

In South Wales:

Llanthony Prima Priory, Monmouthshire, St Kynemark Priory, Gwent, and Peterstone, St Peter’s Priory, formerly St Arthfael’s, Monmouthshire. (West of Newport)

St Kynemark’s (Cynfarch’s)Priory- Llangynfarch’

We have discussed some of the larger Benedictine Priories in Monmouthshire, and then some of the Augustinian foundations. The Augustinian canons who settled in Llanthony , then their later order of Austin Friars of Newport. We now come to a third. About one mile north of Chepstow lie the remains of another small monastic house. St Kynemark, Kinmarchus, Kinmarch seem to be Norman corruptions of ‘Cynfarch’ as some sort of approximate pronunciation, and this house was the one situated a mile North of Chepstow, but was not a church administered from Chepstow Priory.

It lies on the road from Chepstow , but the church lay on high ground.

The ridge reaches a height of 250 feet above sea level providing extensive views over the lower Wye and the Bristol Channel. To the North is Chepstow Park and to the wet the view is blocked by St Lawrence’s Hill and by Cophill. Butler says in his excellent paper for the Historical Journal of The Church in Wales, that the priory lies close to the cliffs bordering the Wye and the head of a steep side valley from the river;It also commands the head of a more gentle valley sweeping down into Chepstow from springs near Kynemark farm, which was built with many of the ruined building stone.

There is a Church dedicated to Cynfarch at Llanfair Dyffryn,Clwyd,which used to have a ‘Sanctus Kynvarch’ represented in a stained-glass window (Benedictine Records, Farmer).Smashed up in the ravages of the 17th century, precious shards have been put together and replaced in the window. There is another church dedicated to St Cynfarch at the Hope Parish at Flint in North Wales.

Disputed Dedication

St John the Baptist is said to have been the dedicatee of St Cynfarch’s Priory and as a hermit himself, living on what God provided in the mountains, plus the fact that most priories became Augustinian Canons, this would seem the most likely dedication. The Catholic Encyclopedia, however, insists that the Priory at some stage became ‘Premontensian’ or Norbertine. We know that from time to time, however, different orders took over different houses, or even that a new order might be given a lease on some of the buildings to commence in an area, but there seem to be no records of the White Canons to substantiate this, unless it was a very ‘ad hoc’ arrangement, as it often was with mendicant Greyfriars or even the Carmelites. Around 1491 the Priory was in financial difficulties and it may be when perhaps a small Norbertine cell may have moved in .The historian Willis Bund described it as Norbertine or Premontensian after considering it similar to Talley in France, and so in the later 15th century, it is possible that the younger order moved in and cared for the older Augustinians there. It is confusing, but there was clearly input from both orders there, overwhelmingly Augustinian, but perhaps the anglicising to Kynemark implies some imput from the monks of the Holy Norbert of Xanten. We may never know. At any rate in the early middle ages St Kynemark or Llangynfarch was a deeply holy place and the Prior seemed to be on a level with the Abbot of Tintern and the Prior of Chepstow in resolving disputes.

My next post will consider how St Cynfarch/Kynemark’s would have looked and its subsequent history.

Petition for the Intercession of St Cynfarch

Seeing that many were brought to Christ by the radiant example of thy virtuous life/ and thy missionary labours, O holy Cynfarch,/ pray that we too may follow thee/ in the service of our Saviour, that our souls may be saved. AMEN

No comments:

Post a Comment