Dingestow-Dingat, Merthyr Dingat, Llandingat-a church stood on this spot from at least the sixth century. Of many Celtic Saints, a number of whom have close associations with Gwent, St Dingat is not one of the famous ones, yet was a true and holy confessor and ordained priest, probably ordained by the authority of Dyfrig (Dubricius) with whose body he travelled to Bardsey or Ynys Enlli when Dyfrig died and was succeeded by St Teilo.

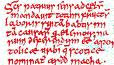

Dingad was, it seems likely educated at Llancarfan under the great and holy Saint Cadoc. The early Bonedd y sant of Penarth 16,15 written down in the 13th century by the Cistercian monks, who collected and for the first time wrote down all this information, and 12 (fourteenth century) and Hafod MS (16) 1400 make DINGAD AB NUDD HAEL one of the holy family of Macsen Wledig.

Macsen Wledig-Maximus of Brittany

Maximus was a distinguished general who served under Theodosius the Elder. He served with him in Africa in 373 and on the Danube in 376. It is likely he also may have been a junior officer in Britain during the quelling of the Great Conspiracy in 368. Assigned to Britain in 380, he defeated an incursion of the Picts and Scots in 381. Maximus was proclaimed emperor by his troops in 383. He went to Gaul to pursue his imperial ambitions taking a large number of British troops with him.

Maximus made his capital at Augusta Treverorum (Treves, Trier) in Gaul and ruled Britain, Gaul, Spain, and Africa. He issued coinage and a number of edicts reorganizing Gaul's system of provinces. Some scholars believe Maximus may have founded the office of the Comes Britanniarum as well.He was given power to rule in the West as Emperor figure.

Macsen had a controversial, if slightly over zealous protection of Christians and Jewish people, despite the intervention of his confessor St Martin of Tours, happily burning heretics, of which the church disapproved. His family he left behind in Britain, seemingly to fend for themselves. What happened to Maximus' family after his downfall is not related. His wife, ( recorded as having sought spiritual counsel from St. Martin of Tours during her time at Trier) Her ultimate fate, and even her name, have not been passed down to history.

The same is true of Maximus' mother and daughters spared by Theodosius., included Anicius Olybrius, emperor in 472, but also several consuls and bishops such as St. Magnus Felix Ennodius (Bishop of Pavia c. 514-21). We also encounter an otherwise unrecorded daughter of Magnus Maximus, Sevira, on the Pillar of Eliseg at Gelligaer, an early medieval inscribed which claims her marriage to Vortigern, king of the Britons.Vortigern is also reputedly buried at Llanvetherine. It is possible that Sevira married a member of the Brychan family in Brecon and that her children produced a King of Usk (Brynbuga) called Nudd, who subsequently produced Dingat. The proximity of the Church of Llanvetherine between Llandingat and Usk seems to add support to their all being of the same family, as Gwytherin was one of his daughters. As always with early accounts and pedigrees, there is room for error but Baring Gould and Fischer (Lives of the British Saints V2 page 344)gives us more details. Nudd’s son, Dingat married Tenoi daughter of Lleudun by whom he had twelve children “who every one served God”. The Myvyrian genealogies (423 and 427) support this-although twelve being a Biblical number, may just indicate a large number of children.

King, Monk,Priest and husband and father-Practise off the Time

In common with Cadoc and common practice of the time, Dingad was both a King, a priest and a founder of his monastery at Llandingat, called Merthyr Dingat in Pope Nicholas’s taxatio. Possibly having reigned until his eldest son was old enough to rule,and following the death of his eife he would have transferred power (as Tewdrig did to Meurig) to his eldest son Lleuddadd and gone on his green martyrdom to his monastic settlement, taking perhaps his wife with him, but certainly enough like minded servants to live out their lives in prayer and contemplation. At this time in the Catholic church there were no rules about priests being married or not, and it was neccessary to provide Christian rulers and leaders in a country which had just come out from the ravishes of Roman civilisation (‘Welsh’ or ‘Welisc’ means ‘Romanised Briton-as they were contemptuously called by the Saxons.His other children were Baglan, Eleri, Tegwy(Tegwyn) ad Tyforiog. It seems to be a confusion, whether Llidnerth,Gwytherin and Ilar were his brothers and sisters or his children.

At some point in the seventh century, because of ‘Martyrdom’ having come to mean only a ‘red’ martyrdom, that the word Merthyr was changed to the word for a holy monastic enclosure or ‘Llan’-not strictly speaking the church or ecclesia (eglwys) but the holy ground separated from the world by a circular or oval wall. Within the llan was the territory of God, outside was the world. The llan did contain a church and dwelling places for the early monks.

Some of these llans were ‘conhospitae’ where married religious dwellt and raised their children. Some were priests, some were not. The discipline of celibacy had arisen on the advice of St Paul, who felt priests had to be free to move around and serve wherever God sent them. They could not be troubled by protecting and providing for a family. St Peter had also left his family to travel with Christ, but they seem to have perished in Rome in Nero’s persecution. Dingat seems to be set in the late fifth century.

Just to repeat for those who have not read the previous blogs:

The Red Martyrdom-the giving of life and blood for Christ. (those who have washed their clothes white in the Blood of the Lamb)

The White Martyrdom-the saint leaves home and family to serve God, wherever God takes him.If wealthy like St Ita of St Ives it may have been a boat or coracle, the wind and waves taking them to their destination-also like St Materiana of Gwent.

The Blue or green Martyrdom-the saint having found his vocational location, then consecrates the llan to God using the rituals and then lives out his liffe in Christian service as a religious, free to marry or not to. Generally there was a powerful link between monarchs because of their learning (often at the best schools such as those at Caerwent and after that at Llancarfan. They also had the means to set up such a place, servants and so forth.Some of them also became ‘red’ martyrs, liek Holy Cadoc himself who was killed.

A Martyrdom or Llan?

The llan at Dingestow (Dingat’s town-Saxon) would have been first cleared-note its proximity to the river, and a wall built. Monks would then live on the land and fast for forty days before the area designated at their holy area was cleared of all evil spirits. They would eat a little milk a little bread and some eggs occasionally and then the original church, sometimes made of stone, but more usually at first out of wood or mud and wattles would be raised and then finally the dwellings. Sometimes beehive huts, but again more usually small mud and wattle cottages.

There was also anotherDingat in a similar llan at Llandovvery, but this was another relative of the Gwent Dingat.

Dingat had given up his life to the service of God and probably was directed by God to this Llan. You can still see the circular outer perimeter of the Llan wall-the division between heaven and the world.All this testifies to a lively faith and Christian witness in Gwent and Glwyssing in the fifth and sixth centuries. It became known as Dingestow when the area was overrun by the Saxons, who seemingly thought more of the market (stow) than the monastery, until they too were brought to Christ by Augustine. The church seems to occur in Pope Nicholas’ Taxatio in the Thirteenth Century.and was probably served by a local secular priest from the diocese of Llandaff who would have lived on the premises.

These priests were ‘rectors’ and the tithes paid to Llandaff, who paid them.In 1390 Father Gregory (ap David)seems to have resigned and Father John (Ap gruffydd) came to take over. There seems to be an unrecorded priest in between, although it is possible Father John stayed for over forty years. In 1432 Father William (ap Philip) appeared but what happened to his successor is unclear. He may have fled to France rather than take the Oath of Supremacy as so many priests did, populating the English Colleges in France. 1539, seems to have been the arrival of the Vicar from the new Church of England, although Masses continued to be said throughout the county at houses like Treowen and in secret covert places known only to Welsh speakers. Raglan Castle and the Earls of Worcester were a powerful Catholic family, who sheltered and harboured priests and where Mass continued to be said until Sit Thomas Fayrfax laid it waste and then the mantle passed to Treowen, who protected the Church , even to regular huge fines imposed upon recusant Catholics.

Ninth Century

It seems a local Chieftain called Tudnab originally built a stone church on this site at this time and bequeathed it to the larger Abbey Church and Chapter at Llandaff ‘In exchange for a heavenly kingdom and for the soul of his father’ , with the Christian name Paul.

Norman Conquest

The church was in existence at the Conquest and even though Llandingat was not given to Monmouth or Abergaveny Priories, a dispute arose for a long time between the dioceses of Hereford, Llandaff and St David , and Pope Callixtus (who canonised St David for his defence of the Catholic Teaching against Morgan (Pelagius) of the Britons) had to intervene confirming the church to Llandaff because of the recorded gift of Tudnab.Pope Callixtus confirmed this claim in 1119.

The New English Anglican Church of Henry VIII

By 1535, the years of the seizure of the monasteries by the king because of their resisstance to his marriage to his mistress, the Deanery of Abergavenny had been established clearly and the boundaries show Llandingat was in it. The Tithes from this church were paid to Llandaff from early times. Many of the beautiful works of art were taken from the church and more probably smashed by Cromwell’s men-demolition men of extraordinary energy. The rood screen would have been removed, from the existence of a small room near the organ, which would have separated the nave from the sanctuary of the church. A small window near the pulpit remains. As the result of the parish having to renovate and maintain such an ancient church from time to time, most of its early features have been removed. The Stoup, from which the Faithful blessed themselves before entering and when leaving church, to remind them of their baptism and consecration to Christ, has disappeared, also the piscine, where the remnants of the consecrated remains of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist, passed directly to the earth. The painting of the Doom over the rood screen has gone as has the originally consecrated stone altar with the stone crosses (probably buried in the churchyard somewhere) There is no reredos, but a beautiful stained glass window.The stone church is spacious and when I visited in February still had its crib out and Christmas decorations. The reason is probably the thick snow that fell here for most of January.

Church Ornaments

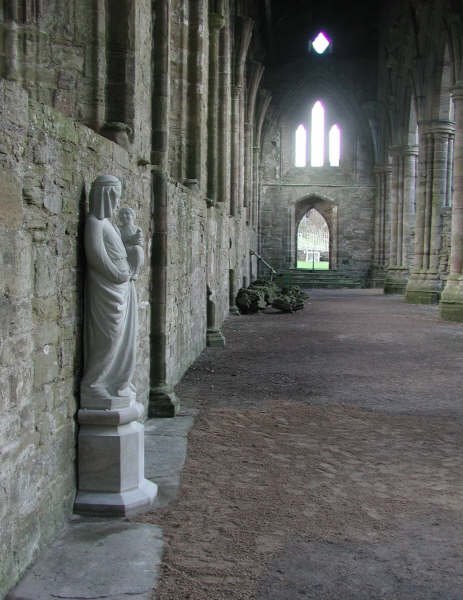

A beautiful statue of the Virgin stands here and a marble statue of St Francis, next to a lovely decoration of pine and church candles. Apart from very colourful stained glass windows, in the Bosanquet family chapel, originally commissioned by the Catholic Jones family of Treowen , is a beautiful white marble statue of a woman grieving, with another spread over her lap prostrate with grief. It is most beautiful. There is also another stone commemorating the death of one of the family during the war.

The Castle

The Castle changed hands several times in baronial troubles in 1283 but in 1256, became part of the Lordship of Monmouth and then to the Crown. It was then attached to the Duchy of Lancaster and in 1465, part of the Lordship of Raglan, and eventual;ly to the 8th Duke of Beaufort who sold it to the Bosanquet family. They lived at nearby Dingestow Court and came from Languedoc in France. The estate had originally been owned by the Jones /Herbert family of Treowen.Sir Charles Jones of Treowen who died in 1637 left a bequest to the Church for the building of the Chapel. He had Mass said at his house all his life and died in the faith. It was important appearances were kept up if Catholics were to be buried in the churchyards of their forefathers. Heavy fines on recusant Catholics meant a later member of the family had to sell off some of his estates to George Catchmayd then to James Duberley and then to the Bosanquets of Essex who came to live at Dingestow and happily take an active interest in local affairs, producing distinguished members, high rranking service men, a Judge, two chairmen of quarter sessions,Common Sergeant of London and Official Referee and several barristers (QCs)as well as clergymen.

Bells

The old Catholic Church would have had a single bell. In 1887, the church had to be restored, obviously in a poor state, in 1847 it was rebuilt from the original with five bells. One of them appears to have been a recast 15th century bell (recast in 1914) and in this year a treble bell was added. Two other bells date from 1656 and 1701.(a new bell cast in Cromwell’s time would have been rare!)A sixth treble bell was added in 1991 in memory of Gillian Vaughan-Best.

Open Church

Delightfully the church was open and I was able to look around.There seems to be a fund to build a public convenience in the church, which was a very good idea. An Ash Wednesday devotion was advertised, and there seems to be a large second hand supply of books at the back of the church and the very useful guide. Of course it is a mixture of 19th century gothic so resembles some older features. The mediaeval priest’s door has been kept, but covered with a curtain. There is a 19th century organ as well. The altar area is very sparse as a simple table with vases of flowers and a medium sized wooden cross. The sedilla or priests sitting area has been replaced by a larger window of bay type although the wide sill could be a seat, and contained many beautiful evergreens and candles.

Visiting-Wonastow Industrial Estate signposted, but do not go in-carry on that road until you arrive at Llandingat, then turn Right to the Church.

All in all the church is a gem. There is parking, and it lies fairly close to the site of the Castle and a short distance from the A40 which you have to leave before the tunnels at Monmouth or if coming from the Newport direction, go into Monmouth on A40 and turn back on yourself at the roundabout, go past the bridge and Momnmouth School on your right and then your first left and turn Right at the top of the Hill, following the road to Wonastow and Dingestow.

Don’t forget to leave a donation if you can afford it................

.JPG)

.JPG)