LAST PART OF CHAPTER ONE:CATHOLICISM IN MEDIAEVAL WALES-please cut and paste into Word as this is a rare article by a Victorian Convert.

Before we proceed to the evidence of later writers and of Mediaeval Welsh literature in general, it will be worth our while to dwell for a moment on the picture of the early Celtic Church , drawn by Gildas in the sixth century. Gildas the author of De Excidio Britannicae, written in a Glamorgan monastery, did not profess to write history. He was a religious and ecclesiastical reformer and he inveighs against rulars and clergy in a savage and merciless spirit. But in spite of the violence of the language , his writings are very important as they contain valuable historical information bearing on the religious condition of the house.

The Work of Gildas

Professor Hugh Williams has dealt very fully and critically with the evidence of Gildas in his ‘Opera Gildas’, and in his’ Christianity in Early Britain’. We cannot do better than quote his estimate of the various historical Quoestiones vexatoe that emerge from the pregnant period in the history of the Celtic Church.Most of the leaders of the nation,spiritual and political, come under Gildas’ unsparing lash- and among them Maelgwyn Gwynedd, the draco insulatis who was in charge of the defences of the country.

Taliesin was chief bard to Maelgwn at his court at the Fortress of Dreganwy, in North Wales. Gildas was himself a monk,and monasticism was already established in the country . In fact, it would seem that it was the religious world outside the monasteries that Gildas criticised so unsparingly.

Now what does he have to say of the Church in his age in Celtic Britain ? What was its Faith? It’s ministry? Its relationship to Rome?

In the words of Mr Willis Bund, was the ‘old Welsh religious system (!)’a kind of foregleam of modern nonconformity?

The historical evidence must decide what the answer has to be , and the evidence is conclusive. Professor Hugh Williams , who was a thorough Protestant writes as follows:

One Church in Britain until 1536, no others. Orthodox Schism in 11th century, but did not affect Britain.

About AD 400 we find that there was in all Christian lands the idea of One Church, called the Catholic Church. Membership of this Church, whether for individuals or for communities, was dependent on the existence of the Faith, and upon general conformity of the existing ecclesiastical order’.

The writer admits that the conception of St Peter, contained in the words already quoted-‘Carae voli Pedyr’ –is found even in Gildas. Passages in the De Excidio show that no other conclusion is possible.

Catholic Celtic Priests were priests in the Catholic doctrine, having their own culture as today.

In his Epistle,eg,Gildas writes in his usual vein of the priests in Britain:

Sacerdotes habet Britannia sed insipientes, sedem Petri Apostoli immundis pedibus usurpantes.

Britain has priests, but they are foolish, usurping the Chair of Peter, the Apostle with unclean feet.

The Priesthood is referred to as the sacerdotalis dignitas, St Peter is designated as Prince of the Apostles- ‘princeps apostulorum beatus Petrus’.

In the Vita Gildae he himself gives an account of his journey to Rome ‘to invoke the merits of the Blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, that, by their intercession, he might obtain from the Lord pardon for his sins.’

Belief in the Primacy of Peter. Celtic priests made frequent visits to both Rome (st Cadoc seven times in the reign of seven popes)and Jerusalem.

A still more convincing and pertinent testimony to the contemporary belief in the primacy of the see of Peter is conveyed in another passage from the Epistle of Gildas ‘’Petro ejusque successorioribus dicit Dominus;et tibi dabo claves regni coelorum’ (The Lord himself designated Peter and his successors with the words 'To you do I give the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven'.

He describes the Holy Eucharist as ‘sacrificial worship’.

In his criticism of the church in Britain,he complains ‘ that they seldom sacrifice (say Mass) and never stand amid the altars with a pure heart.-‘(raro sacrificantes et numquam puro corde inter altaria stantes’).

In connection with the word ‘altaria’ Professor Hugh Williams if of opinion that even in the time of Gildas there were probably , in some at least of the British Churches , several altars-a fact of some significance in relation to the position of Mass in early Celtic Christianity.Gildas calls the altar ‘The Seat of the Heavenly Sacrifice’.

Mass was lengthy and ornate (Stowe Missal and Antiphonary of Bangor are examples)T

here are extant no liturgical books to supply us with information concerning the ceremonials of the Mass in the British Church of that period, but we are told that some idea of its ornate and perhaps lengthy character may be obtained from the Gallic Mass of Saint Germain the Irish Stowe Missal-which was in use before the coming of St Augustine-and the Antiphonary of Bangor.

Ordination-priest's primary function was to say Mass

At their ordination, the hands of the priests were anointed with oil.

‘The hands of priests’ says Gildas,’are blessed so that they may be reminded not to depart from the precepts which the words express in the consecration’.

On this, the editor of Gildas makes the following illuminating comment:-

‘The idea that they were priests as representative of the priesthood of believers finds no countenance in Gildas. The function of the priest, in the words of Missale Francorum of the same age was ‘ut corpus et sanguinem Filii Tui immaculate benedictione transformet’.It is therefore evident that in Gildas’s time the essential function of the priest was to offer the great sacrifice, the Sacrifice of the Altar.

Everyone prayed for the souls of the departed Brothers and Sisters (maccabees 2)

With regard to the Catholic custom of praying for the dead, there is no need to collect the historical testimonies on this point. The conclusion arrived at by Warren in his valuable work on The Ritual and Liturgy of the Celtic Church covers the whole field with which we are dealing.’ Praying for the dead was as recognised a custom of the ancient Celtic Church as in any other portion of the primitive universal or Catholic Church’.

The antiquity of this custom in Wales is beyond doubt or evil, but what is equally important is that it has survived almost to modern times among the Welsh Peasantry.

The Gwylnos or wake , which has now resolved itself into a prayer meeting, is really a lineal descendant of the Officium Defunctorum-namely , the Placebo and Dirge. The declaration ‘nefoedd iddo’ at the grave on the Sunday following the burial if the Welsh equivalent of ‘Requiescat in Pace’.

As regards Bardic literature, there is a total blank between the sixth century and the eleventh. After the return from Ireland of Gruffydd ap Cynan in the North and in South Wales of Rhys ap Tewder from Britanny, there was a marked revival of bardism, but the intervening period is mute (possibly because of the frequesnt raids by Saxons and then Vikings and frequent burnings of monastery libraries)

Nevertheless, it is important to remember that,while the Welsh records of this period have now disappeared , they still existed in the time of the literary revival in Norman times; for the bards and writers of the new era had undoubtedly access to many old Welsh records.

Nennius -the link

Quotations from the early mediaeval bards in confirmation of this can be found in Sharon Turner’s ‘Vindication of the Ancient British Poems’ to which the reader is referred. Nennius, the author or editor of the Historia Britonum is an important link between te sixth century group of Welsh Bards-Taliesin, Llywarch Hện,Aneurin, Merlin etc- and the Laws of Hywel Dda and the times of Giraldus Cambrensis; and he had undoubtedly access to old British records then extant, for he mentions the antiques libris nostrorum. His date is about AD 800.

Asser of Menevia

It is unfortunate that the learned Asser of Menevia , monk and probably shop of St David’s has in this De rebus gestis Aelfredi left us so little information about the religious condition and customs of his native family.

Early Writers and Bards did have historical records, some not available to us today.

Rhygyfarch

There is no doubt that Rhygyfarch, son of Sulien, Bishop of St David’s and the eleventh century biographer of s David, had at his disposal some authentic records preserved in the cathedral library, which had escaped the ravages of the ferocious sea rovers.

Gerald the Welshman

Giraldus Cambrensis ,hoever, leaves us in no doubt as to the existence at his time of quitea considerable body of ancient Welsh manuscripts.

‘This’ he says ’seems remarkable to me that the Cambrian bards have genealogies, etc….in their ancient and authentic books written in Welsh’.

William of Malmesbury gives similar evidence:’ it is read in the ancient accounts of the actions of the Britons.’

And again ‘These things are from the ancient books of the Britons’.

The reasons why one desires to make clear the point touching the authenticity of the early Welsh records must be obvious. It gives addred weight to the testimony of the literary documents that have survived from the orman period in regard to the early ecclesiastical position of Wales.

The ancient Welsh records have perished for us but they had not perished for the poets and the chroniclers and ecclesiastical writers of the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Inference they are legends does not disguise their Catholic traits

It is true that legendary matter is mixed up with the meagre records of the lives of the Welsh Saints and romance with thLeaving the facts of Welsh history, but no amount of legend and romance can altogether obscure the main lineaments if the deep rooted realities of the religious life of the Welsh people. This life-the spiritual side of the nation-is necessarily written on too large a scale to be seriously affected by the periodic intrusion of the spirit of romance or other form of literary revivals.

Y Mabinogi is Catholic in Spirit

Leaving aside the scanty remains of the Taliesin and Merlin group of sixth century bards, early Welsh literature naturally takes the form of romance; and in the old Welsh romances, the Mabinogion , the Arthurian stories and the legend of the Holy Grail- we do not expect to find much authentic history as conceived by the prosaic chronicler; but even the old writers of romance could not write their productions in a sort of psychological vacuum. Although they do not supply us with precise historical records, like the Annales Cambriae of Brut y Tywysogion they could not help letting in the persuasive atmosphere of the age in which they lived and wrote; and thus revealing some of the deeper and finer aspects of contemporary history, especially in regard to social customs and religious belief.

This is a point of some importance, for it enables us to take thse old Welsh romances in hand as sources of trustworthy information in regard to the ancient faith of the Cymry. We gather, therefore, from them that the atmosphere of the earlyromances is tha of the Catholic Church, with a pronounced monastic character. In the background we have knight errantry and the institutions of chivalry, though the latter is more characteristic of the later of the earlier forms, and belongs to Norman times.

Some of the Mabinogion probably represent a period of very high antiquity, perhaps pre Roman; but in their final form they are permeated with the spirit of Catholic antiquity, and present all the intimate features of a long established Catholic community.

The Blessed Virgin Mary

A few typical instances of this must suffice. As it has been asserted by some writers on Welsh literature that the Cult of the Blessed Virgin is a product of Norman times, it is instructive to note that Nennius (ninth century) in his Historia Britonum which may be considered as the ‘fons et origo’ of the body of the legend and romance subsequently developed and polished by Geoffrey of Monmouth and others, states that King Arthur , in going to battle, wore the image of the Blessed Virgin on his shield. The original word is ysgwydd (shoulder) but this is a copyist error for ysgwyd, shield(scutum).

In the “Legend of the Holy Grail”,again,the Grail is the natural centre point of all the symbolism of Mass and Sacrament , and the three Grail Keepers represent the Holy Trinity.

Llantwit Major /Llanilltud Fawr

It will be of interest to Welsh people to know that the locus of these wonderful Grail Stories is probably in the neighbourhood of Llantwit Major, which even today has preserved to a great extent the outward marks of its high antiquity and romantic history. In the Grail legend the characters live and move in the odour of Catholic sanctity; they are represented as going daily to Mass before starting on the knightly enterprises of the day. One of the characters declares,for example,’’I am a Knight. One of the Quest for the Holy Grail’. There are many of the Quest labouring in vain, for they are sinners, without inclination to go to Confession. No-one shall see the Holy Grail except it be through the gate that is called Confession’’.

The following are typical quotations:

“When he had confessed and taken his penance, he besought the holy man for the sake of God to give him his Lord’s Body -‘rhoddi iddo Gorph yr Arglwydd’.”

Again, “Peredur (Percival, Parsifal)was delighted to see the people believing in God and Mary”.

Yr Offeren-The Mass

This is a phrase constantly used in the San Greal as well as in later Bardic literature. It was also used in Forms of Bequest. There is also a reference in the San Greal to the Mass of the Blessed Virgin, the term for Mass being ‘offeren’.As words are the symbols of religious beliefs, it is important to notice, as the term ‘offeren’ is sometimes confused with ‘offrwm’ by modern writers in dealing with the history of the Holy Eucharist, that in early Welsh Literature no such confusion is to be found.

Offrwm which is a generic term for ‘offering’ is never confused with ‘offeren’, which is a specific term for the highest offering in the Chritian faith, the Sacrifice of the Mass.

A passage from the San Greal itself illuminates this distinction:

“Yna gwrandaw offeren aoruc ef cyn y fynet, a phawb a aeth yngaredic y offeren yr anrhdedd idaw.”

(He went to hear Mass before going , and all went kindly to offer the honour to Him)

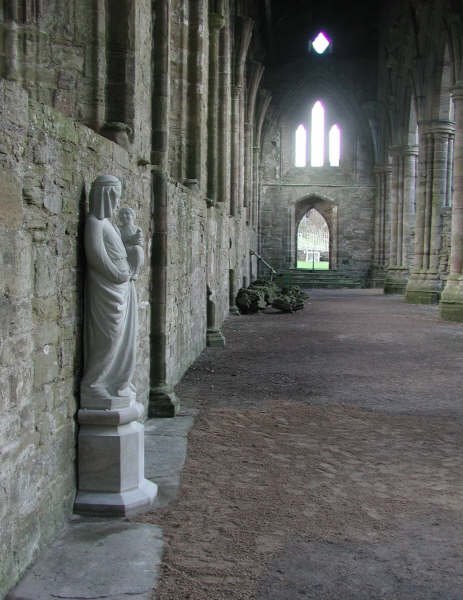

If we now turn to formal historical treatises such as the Bruts, we find he same features, the same empathetic testimony to the belief and devotional practices of Catholicism. The importance of the Mass in the national life is illustrated by such an entry as the following in Brut y Twysogion:

“Gwedy hyny nos wyl Fair y Canwylleu y cant |Esgob Mynyw Efferen yn ystrad Flur, a hono a fu yr Efferen gyntaf a ganawd yn yr Esgobawt”.

“On the Feast of Candlemas, the Bishop of Menevia sang Mass in Strata Florida; that was the first Mass he sang in the diocese.”

This was a very appropriate record, considering that Strata Florida, the Cistercian Abbey at the foot of Plynlimmon, and the ‘Westminster Abbey of Wales’ in olden times, was the home of this particular chronicle.

The moral of an entry of tis kind is very clear. The Welsh Brut only professed to register events of national importance. Such an event was the first occasion of ‘canu offeren’ by a Welsh Bishop in that particular Monastery.

___________________________________________

2 comments:

I don't know what comment this is supposed to be, but it is not an intelligent one, so God Bless you and bring you to understanding.

Post a Comment